Insider secrets

“A rule of thumb is that high returns require high risks, but many smart people will ignore this common sense when promised that they can get 15 percent returns with low risk. A 9 to 12 percent return over the last decade in the stock market is about as good as anyone did.” - John Micetich

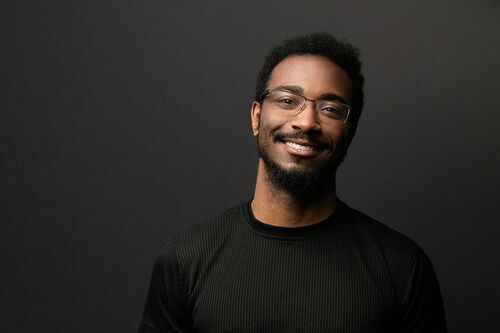

It is 5 p.m. on a Monday night and John Micetich (BS, '69, psychology) is getting his second wind. Good thing because the 20 students straggling into the room—all seniors—look as if they need the carbohydrate boost they'd be getting if they hadn't skipped dinner to attend his finance class. They drop into their seats and cast a weary glance at the outline he is writing on the chalkboard.

"They've asked me to put my notes on the Web," says Micetich with a shrug. "But I prefer chalk, paper, and pen. I guess it dates me."

This gripe is the students' only one because at 55, Micetich has an enviable track record in financial planning. He has helped hundreds of people with modest to high incomes accumulate wealth by avoiding risky trends in favor of proven practices. A 1969 graduate of the College of LAS in psychology and 1974 MBA graduate of San Diego State University, he pursued a career in banking and financial planning that took him around the world and through numerous swings in the economy. Since 1985, he has run his own investment-advising firm, Kensington Financial, for which he manages some $60 million in assets.

So that students may also enjoy similar success, he packed up his house in San Diego last January and migrated with his wife to UI for the winter, where he taught a nine-week course in financial planning—pro bono. He has taught a related class at the University of California, San Diego, for 13 years. He approached the College of LAS about bringing the popular class to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign because he wanted to give something back to the university that gave him his start.

"I wanted to do more than just give money," he says, "and this is something I am good at and which will be important to students sooner than they think. A few months from now when they get their first job, they'll have to make choices in a cafeteria plan of choices, within the first 90 days, that will affect their future. Given all the job uncertainty graduates face today, smart money decisions are one way they can reduce their risks."

Micetich's official title is adjunct professor in the College of Business, which was arranged after the College of LAS approached David Sinow, also an adjunct professor in CBA, who readily found a niche for Micetich in their finance curriculum. What appealed to Sinow was the breadth of Micetich's real-world experience.

How things such as risk play out in the marketplace is one example. "A rule of thumb is that high returns require high risks, but many smart people will ignore this common sense when promised that they can get 15 percent returns with low risk. A 9 to 12 percent return over the last decade in the stock market is about as good as anyone did."

He keeps the class lighthearted, pointing out to the men in the room that women tend to be the best investors because they don't let their egos get involved. Balanced, long-term investing is the message he sends. While not sexy, it pays off in the long run.

The 22-year-olds in this class and the 30- and 40-somethings who usually enroll in his night class in California are remarkably similar, says Micetich, who consistently wins awards for his teaching. "My adult class has more life experience but very similar misconceptions about investing. The main difference I noticed is that I had to update my anecdotes for the younger crowd. I replaced stories about Warren Buffett with Enron because the students had no clue who Warren Buffett was."

Micetich will return this winter to offer an LAS-only class. He will modify the curriculum for these non-business majors and incorporate a lesson he learned while at University of Illinois in the 1960s. "Challenge things," he says. "I want them to challenge everything. If their professor tells them money is good, I want them to ask him why. This kind of critical approach will make them good investors."