Brazilian studies gets broad attention at Illinois

Think Brazil and you might think beaches, rain forest, the 2016 Olympics – all far removed from central Illinois.

Yet the University of Illinois is perhaps the most comprehensive center of Brazilian studies in the U.S.

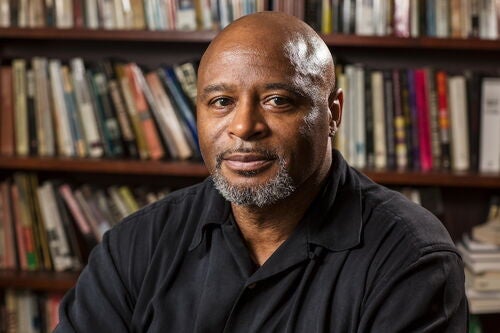

Illinois’ research and teaching connections with Brazil are “distinctively broad,” said Jerry Dávila, director of the university’s Lemann Institute for Brazilian Studies. They involve faculty and students from agriculture, business, engineering, education, community health and the liberal arts, among others – even the Prairie Research Institute and Illinois Water Survey.

Faculty are engaged in more than 90 research collaborations with dozens of higher education institutions and research institutes in Brazil. Studies among those range from post-harvest soybean loss, to the effect of natural fungicides on common trees, to how one region’s music relates to its drought-stricken landscape, to language acquisition, vulnerable youth, biofuel mandates, tourism and politics.

The Illinois model is “a very unusual footprint for Brazilian studies (at a U.S. university), which frequently takes place in only a handful of humanities and social sciences,” Dávila said. “It reflects the kind of extraordinary breadth that this kind of land grant university provides.”

The Lemann Institute was established only six years ago, in 2010, but Brazilian studies at Illinois was already well developed, Dávila said. The relationship between Brazil and the U. of I. reaches back to the early 1890s, when Eugene Davenport, who would become Illinois’ first dean of agriculture, went to São Paulo and advised coffee planter Luiz de Queiroz on establishing Brazil’s first school of agriculture.

That relationship between the two institutions would continue. The agriculture school became part of the University of São Paulo, which has been the site of more than a dozen research collaborations with Illinois in recent years. (Schools in Rio de Janeiro are the site for at least nine collaborations.)

The U. of I. Library also developed an early focus on Brazil, Dávila said, enhanced further after World War II, when it was designated as the prime collector of materials on Brazil under a federal acquisitions program called the Farmington Plan. As a result, the library contains more than 100,000 related titles, “making Illinois one of the most unique and extensive places to find sources on or from Brazil anywhere outside of that country,” Dávila said.

Brazilian studies at the U. of I. also has benefitted from the leading roles of two faculty members: history professor Joseph Love, now emeritus, and economics professor Werner Baer, who died this year.

Love “undoubtedly made the University of Illinois, for a long time, one of the leading institutions for the study of Brazilian history in the U.S.,” Dávila said. Baer produced “this very dense ecosystem of Brazilian students of economics and professors of economics going back decades,” as well as several prominent central bankers, one a recent president of the Central Bank of Brazil and now the country’s representative to the International Monetary Fund.

In addition to its support for research, the Lemann Institute provides fellowships to Illinois and Brazilian students, both graduate and undergraduate; organizes international conferences on Brazilian topics; and supports cultural activities and study abroad opportunities. Its participation in the Brazil Scientific Mobility Program, funded by the Brazilian government, has brought more than 200 Brazilian students to study at the U. of I. over the last few years.

“What’s really special about our program is that it reflects the DNA of the university,” Dávila said, by bringing a “broad interdisciplinarity” into the field of Brazilian studies, which “drives new kinds of conversations. I think we are practicing that in a way that really is a model.”