Professors help Police Training Institute address racial bias

In early 2014, months before the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and shortly after the Black Lives Matter movement began, the Police Training Institute at the University of Illinois, with help from professors in LAS, began offering police recruits classes that challenged their views about race and racism, introduced them to critical race theory, and instructed them in methods to de-escalate potentially volatile encounters with members of minority groups.

The Policing in a Multiracial Society Project, an optional 10-hour class to which many Illinois police chiefs send their recruits, asks new officers to ponder, for example, their own and others’ innate racial biases, and offers evidence of the harm that can come from incorrect assumptions about race and racism.

The PTI trains police recruits from about 500 police departments in the state of Illinois. Rather than adopting a military approach to training, PTI uses an adult-learning model, encouraging interactive learning and integrating scenario-based role playing into every aspect of training.

Michael Schlosser, director of the PTI, and his colleagues describe the course in a paper in the International Journal of Criminal Justice. (Watch a video about the training.)

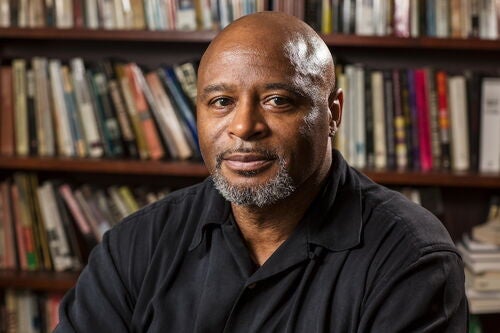

Schlosser designed the course with Sundiata Cha-Jua, a professor of African American studies and history; Helen Neville, a professor of African American studies and of educational psychology; community member Imani Bazzell; and student Maria Valgoi. He and his colleagues are studying whether the training meaningfully alters racial awareness in a mostly white, mostly male police force.

That evaluation involves questions from the Colorblind Racial Attitudes Scale, a tool developed by Neville. The CoBRAS questionnaire assesses a respondent’s tendency to acknowledge (or dismiss) racial bias in their own lives and in society in general, Neville said.

“Although some people think it’s good not to ‘see race,’ findings using the CoBRAS and similar scales suggest that to deny, distort or minimize the existence of racism is related to greater racial intolerance and old-fashioned racist beliefs,” she said.

Other research has demonstrated that police racial attitudes are pliable. Perhaps the most compelling example is a 2012 study of New York City police officers who took a semester-long ethnic studies course. The researchers found that, on average, white police officers’ colorblind racial attitudes had shifted meaningfully by the end of the class. Their CoBRAS scores moved closer to those of minority officers, who, not surprisingly, were less likely to subscribe to colorblind racial beliefs in the first place.

Schlosser is trying to improve upon that outcome. The free, optional training available at the PTI adds 10 hours to the police recruits’ 12-week training. Roughly 75 percent of the more than 500 police chiefs who send their recruits to the PTI now elect to include the new training.

Schlosser and his colleagues have adjusted the training program, giving recruits more time to share their ideas and attitudes about race and policing; bringing in African-American and other speakers who were arrested, convicted and jailed for crimes they didn’t commit; and role-playing with an experienced team of trainers (many of them African-American) who walk young recruits through a variety of potentially volatile scenarios, many of which include a racial component.

The team is gathering data on the new training regimen, evaluating recruits before and afterward to see if this approach has more success.

Schlosser points to figures from the Department of Justice Bureau Statistics that indicate 98 percent of police interactions involve no force at all, and the odds of a police officer shooting someone is just 0.03 percent. That doesn’t dampen their resolve to address the issue, however.

“We hope to minimize, through training, the influence of racial bias in police decision-making,” he said.