Professor reflects on death row experience in post-revolutionary Iran

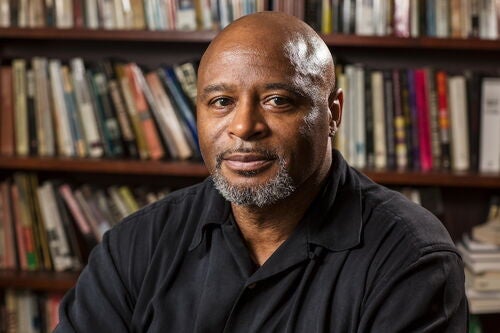

Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi has written plenty about the Iranian Revolution and its aftermath, including two scholarly books. But the University of Illinois professor also lived that history as an activist and then political prisoner, and now has his own evocative story to tell.

In a new autobiographic novel or “novelistic memoir,” Ghamari (the last name he uses with this book), a professor of history and of sociology, contemplates on three years he spent on death row in the early 1980s in Tehran’s infamous Evin prison—years of torture, deprivation and indignities, during which he saw many cellmates marched off to executions, and thought more than once that his own time was near.

“Remembering Akbar: Inside the Iranian Revolution” was published in September by OR Books

The title is “Remembering Akbar: Inside the Iranian Revolution,” with “Akbar” the name Ghamari used as a leftist student activist during the years immediately before and after the revolution. He had shared the objectives of the Islamic revolutionary movement, including the overthrow of the Shah, but did not subscribe to the movement’s ideology. Continuing his activism after the revolution, he found himself on the wrong side of those in power.

“Remembering Akbar” was not a book that Ghamari ever intended to publish. But every New Year’s Eve, the anniversary of the day in 1984 when he was freed, he made a ritual of using that day to meditate and write about his experiences.

He shared each year’s story with a growing list of friends. “Everyone told me these are really interesting pieces, they have literary value, they have historical value,” he said.

Still, Ghamari was reluctant to share them with a wider audience, in part because he didn’t want them appropriated as part of the U.S. conflict with Iran. “I really didn’t want this to become somehow a part of that kind of politics … justifying a more nonpeaceful, shall I say, relationship with Iran,” he said.

He also needed time to “reflect back and make sense of that life,” he said. “People would ask me, ‘How could you do all these things?’ or ‘How could you bear all those things that happened to you?’ And I really don’t know … in so many different ways I feel like that person was not me.”

Ghamari describes horrors not uncommon in other prison and prison camp memoirs from other times and places—most of which he experienced while cancer was also invading his body. Unlike many books in the prison camp genre, however, he said his was not written as an indictment of his captors or those in power.

“I try to present it in a more universal political context, rather than saying that this awful regime was doing this. I wanted to go a little bit above that,” he said.

“I'm not trying to indict anyone. I'm just trying to show through my writing what happens to people when they find themselves in these very intense circumstances—the way they react, the way they relate, the way they betray, the way they love, the way they die and the way they suffer,” he said.

“Remembering Akbar,” published in early September by OR Books, just happens to follow within weeks of the author’s latest scholarly book on the revolution, “Foucault in Iran: Islamic Revolution after the Enlightenment.” Published under the last name Ghamari-Tabrizi, it looks at the Iranian revolution from outside the usual assumptions of the Enlightenment or of progressive discourses of history.

“One always wonders why revolutions don’t happen more often, because revolutions are really a rare thing in history,” Ghamari said. “And when they happen, everybody sort of goes back to their tool kit for understanding them.” Instead, they need to step outside that tool kit and understand that every revolution is unique, he said.

Ghamari said he hopes “Remembering Akbar” also provides a valuable study for understanding revolutions, but from a personal level. “It’s very hard for people, when they read about revolution, to understand what it takes to be a revolutionary and how it transforms peoples’ lives in so many different ways,” he said. “This is a book of history from below, about how history is experienced, how revolutions are lived by people who take part in them.”