Researchers solve the puzzle of a missing river

For hundreds of years, the cold and wide Slims River, at some points 150 meters across, has carried meltwater northward from the Kaskawulsh glacier in Canada’s Yukon Territory to join Alaska’s Yukon River, where it would snake toward the Bering Sea. Jim Best recalls the strange and dusty day when he discovered the Slims River had virtually disappeared.

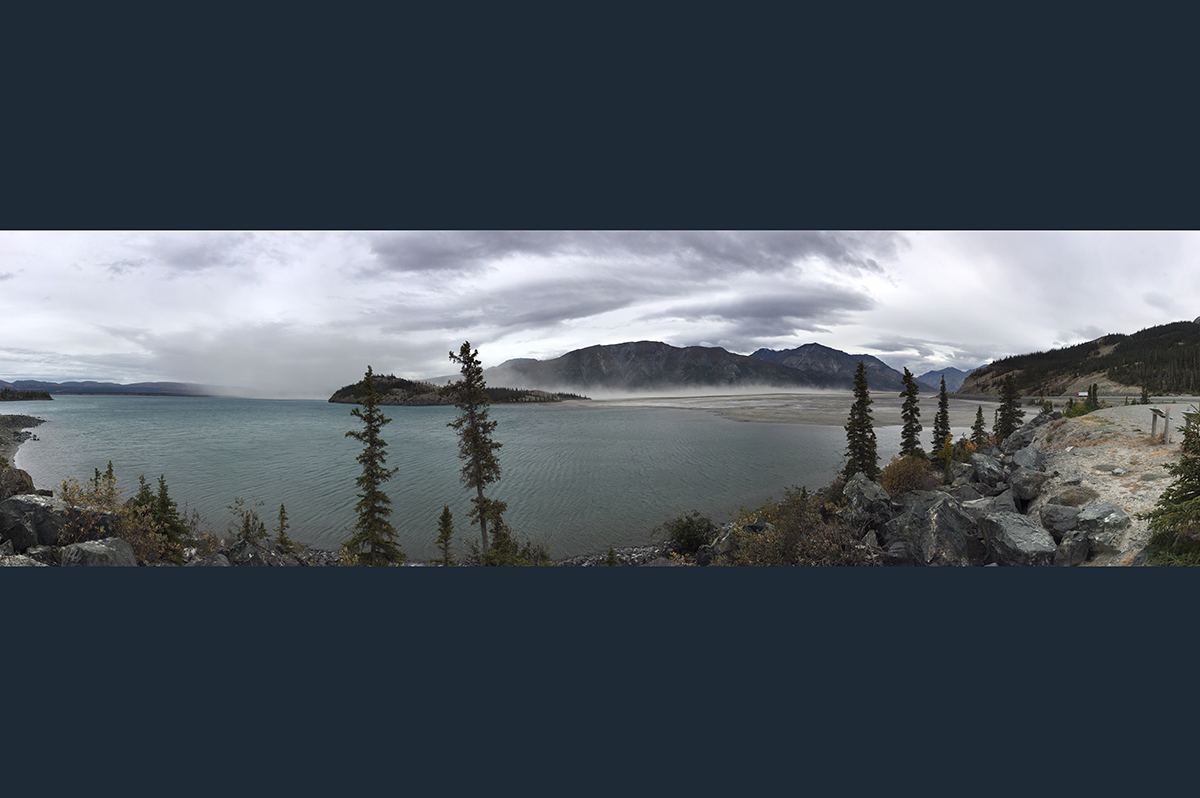

The top of the Slims River delta, once submerged by water, was laid bare. Strong afternoon storms whipped up the exposed sediments into dense storms, and the dust-rich air swirled into researchers’ mouths and nostrils.

“We had previously conducted research in the area in 2013, but on our return in summer 2016 we found a vastly different landscape where the former Slims River entered Kluane Lake,” said Best, the Jack and Richard Threet Professor of Sedimentary Geology and professor of geography and geographic information science at Illinois, “The river had virtually dried up and the lake into which the river flowed had dropped in water level.”

It was a case of what geologists call river piracy, which has been documented before, but only as a process that has occurred over many hundreds or thousands of years. Never before had it been observed in such a dramatic and speedy fashion: River gauges at the Slims River mouth indicated that the disappearance had occurred over four days from May 26 to 29, 2016.

"Geologists have seen river piracy, but nobody to our knowledge has documented it happening in our lifetimes," said Dan Shugar, a geoscientist at the University of Washington Tacoma, who studied the event with Best. "People had looked at the geological record — thousands or millions of years ago — not the 21st century, where it's happening under our noses."

Best and Shugar, along with John Clague at Canada’s Simon Fraser University, and three other colleague, set out to determine what happened. Their findings were reported on April 17 in Nature Geoscience, and the disappearance of the Slims River is being called the first known case of river piracy in modern times.

The event was traced to the nearby, massive Kaskawulsh Glacier, which has retreated about a mile up its valley over the past century. Last spring, its retreat triggered a geologic event at relatively breakneck speed. The toe of ice that was sending meltwater toward the Slims River and then north to the Bering Sea retreated so far that the water changed course, joining the Kaskawulsh River and flowing south toward the Gulf of Alaska.

Shugar, lead author of the study, and Best and Clague, who co-authored the paper—now being reported widely in media as a disturbing consequence of worldwide climate change--had planned fieldwork last summer on the Slims River. When they arrived, however, the river was not flowing.

By late summer, "there was barely any flow whatsoever. It was essentially a long, skinny lake," Shugar said. "The water was somewhat treacherous to approach, because you're walking on these old river sediments that were really goopy and would suck you in. And day by day we could see the water level dropping."

The research team used their aerial mapping drone to create a detailed digital elevation model of the glacier tongue and headwater region.

“We headed by helicopter to the terminus of the glacier,” Best said, “and found a new landscape there as well, with a fresh ice-walled canyon having formed at the front of the ice, with nearly all the flow now entering a different river, and leaving the Slims River with very little flow. We were able to deploy our mapping drone to collect unique imagery from which we could construct a map of the new glacier terminus.”

For the last 300 years, Shugar said, Slims River flowed out to the Bering Sea, and the smaller Kaskawulsh River flowed south to the Gulf of Alaska. But researchers found that the glacial lake that fed Slims River had actually changed its outlet.

"A 30-meter (100-foot) high canyon had been carved through the terminus of the glacier,” Shugar said. “Meltwater was flowing through that canyon from one lake into another glacial lake, almost like when you see champagne poured into glasses that are stacked in a pyramid."

That second lake drains via the Kaskawulsh River in a different direction than the first. The situation is very unusual, Shugar said, since the glacier's toe was sitting on a geologic drainage divide.

Clague began studying this glacier years ago for the Geological Survey of Canada. He observed that Kluane Lake, which is Yukon's largest lake, had changed its water level by about 12 meters (40 feet) a few centuries ago. He concluded that the Slims River that feeds it had appeared as the glacier advanced, and a decade ago predicted the river would disappear again as the glacier retreated.

"The event is a bit idiosyncratic, given the peculiar geographic situation in which it happened, but in a broader sense it highlights the huge changes that glaciers are undergoing around the world due to climate change," Clague said.

The geologic event has redrawn the local landscape. Slims River crosses the Alaska Highway, and its banks were a popular hiking route. Now that the riverbed is exposed, Dall sheep from Kluane National Park are making their way down to eat the fresh vegetation, venturing into territory where they can legally be hunted. With less water flowing in, Kluane Lake did not refill last spring, and by summer 2016 was about one meter (three feet) lower than ever recorded for that time of year.

Waterfront land, which includes the small communities of Burwash Landing and Destruction Bay, is now farther from shore. As the lake level continues to drop researchers expect this will become an isolated lake cut off from any outflow.

On the other hand, the Alsek River, a popular whitewater rafting river that is a UNESCO world heritage site, was running higher last summer due to the addition of the Slims River's water.

Shifts in sediment transport, lake chemistry, fish populations, wildlife behavior and other factors will continue to occur as the ecosystem adjusts to the new reality, Shugar said.

"So far, a lot of the scientific work surrounding glaciers and climate change has been focused on sea-level rise," Shugar said. "Our study shows there may be other underappreciated, unanticipated effects of glacial retreat."

The Kaskawulsh Glacier is retreating up its valley because of both readjustment after a cold period centuries ago, known as the Little Ice Age, and recent industrial-age warming due to greenhouse gases. A technique published in 2016 shows a 99.5 percent probability that this glacier's retreat is showing the effects of modern climate change.

Best said the river piracy occurred in a “geological instant.”

“Retreat of the glacier reached a threshold, or tipping point, where such large-scale river channel change could take place,” Best said. “This demonstrates how some environmental changes may be exceedingly rapid, but as a result of longer-term change, that we here ascribe to global warming within the industrial era.”

He added: “Our results also show the huge importance of being able to study and quantify such environmental change, and its causes, as we seek to better understand, predict and cope with, the potential impacts of such events.”

Other co-authors are Christian Schoof at the University of British Columbia, Michael Willis at the University of Colorado and Luke Copland at the University of Ottawa. The study was funded by the University of Washington Royalty Research Fund, Parks Canada, Yukon Geological Survey, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the University of Ottawa, and the University of Illinois.

The event has been widely reported in media, including The New York Times, Washington Post, The Guardian, CBC, ABC, and Inside Climate News. For more information, contact Best at jimbest@illinois.edu.