Astronomers at Illinois shed light on how galaxies formed

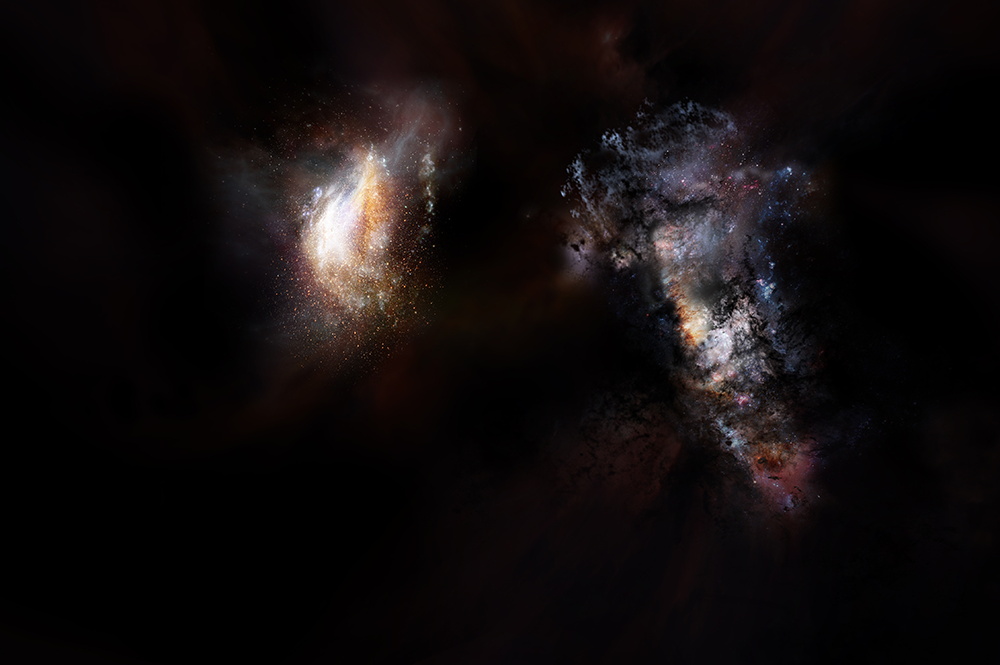

Astronomers have discovered surprising examples of massive, star-filled galaxies seen when the cosmos was less than a billion years old which challenge assumptions about how the universe formed.

Observations with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, conducted by a team of astronomers including several at Illinois, have identified two giant galaxies seen when the universe was only 780 million years old, or about 5 percent of its current age.

The two galaxies are in such close proximity — less than the distance from the Earth to the center of our galaxy — that they will shortly merge to form the largest galaxy ever observed at that period in cosmic history. This discovery provides new details about the emergence of large galaxies and the role that dark matter plays in assembling the most massive structures in the universe.

The researchers report their findings in the journal Nature.

Astronomers have long expected that the first galaxies, those that formed just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, would share many similarities with some of the dwarf galaxies we see in the nearby universe today. These early agglomerations of a few billion stars would then become the building blocks of the larger galaxies that came to dominate the universe after the first few billion years.

Ongoing observations, however, suggest that smaller galactic building blocks were able to assemble into large galaxies quite quickly.

“With these exquisite ALMA observations, astronomers are seeing the most massive galaxy known in the first billion years of the universe in the process of assembling itself,” said Dan Marrone, associate professor of astronomy at the University of Arizona in Tucson and lead author on the paper.

Astronomers are seeing these galaxies during a period of cosmic history known as the Epoch of Reionization, when most of intergalactic space was suffused with an obscuring fog of cold hydrogen gas. As more stars and galaxies formed, their energy eventually ionized the hydrogen between the galaxies, revealing the universe as we see it today.

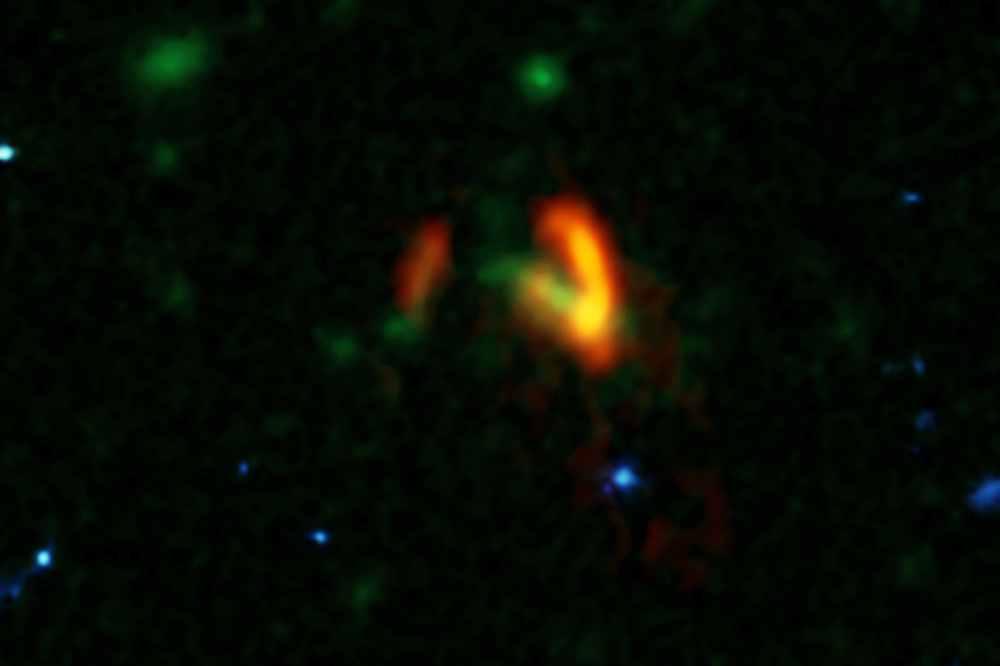

The galaxies that the astronomers identified, collectively known as SPT0311-58, were originally identified as a single source by the South Pole Telescope, which Joaquin Vieira, a professor of astronomy at Illinois and a co-author on the study, helped build while he was a graduate student. A graduate student from Illinois is currently stationed at South Pole Telescope.

These first observations indicated that this object was very distant and glowing brightly in infrared light, meaning that it was extremely dusty and likely going through a burst of star formation. Subsequent observations with ALMA revealed the distance and dual nature of the object, clearly resolving the pair of interacting galaxies.

“There are more galaxies discovered with the South Pole Telescope that we’re following up on,” said Vieira, “and there is a lot more survey data that we are just starting to analyze. Our hope is to find more objects like this, possibly even more distant ones, to better understand this population of extreme dusty galaxies and especially their relation to the bulk population of galaxies at this epoch.”

He added: “It is excruciatingly difficult to observe the starlight from these distant, dust-obscured galaxies with existing facilities — even with the Hubble Space Telescope. ALMA has opened a new window into observing the dust-obscured universe. The launch of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope next year will finally enable us to observe the stars in these galaxies and better understand how they relate to galaxies in the present day.”

Vieira said that the James Webb Space Telescope, which will observe the universe after being launched by rocket into space, is the largest, most ambitious, and most expensive space telescope ever built. Vieira will be among the first astronomers to conduct observations with the space telescope.

Illinois’ footprint in the current study is deep, Vieira noted. Other co-authors include two Illinois graduate students, Sreevani Jarugula and Kedar Phadke, and an undergraduate student, Sidney Lower, who is majoring in physics in the College of Engineering. Another co-author on the study is an Illinois alumna, Katrina Litke (BS, ’15, astronomy and physics).

Lower said that her contribution was taking mass estimates of various types of sources from the literature and comparing them with gas and dust mass estimates of SPT0311-58, producing a plot that appears in the paper.

“We see that even though SPT0311-58 exists in the early universe, its galaxies are the most massive dusty galaxies we’ve seen, which is an exciting mystery that we’re trying to solve. How did they get this massive in such a short time?” Lower said.

To make this observation, ALMA had some help from a gravitational lens which provided an observing boost to the telescope. Gravitational lenses form when an intervening massive object, like a galaxy or galaxy cluster, bends the light from more distant galaxies. They do, however, distort the appearance of the object being studied, requiring sophisticated computer models to reconstruct the image as it would appear in its unaltered state.

This “de-lensing” process provided intriguing details about the galaxies, showing that the larger of the two is forming stars at a rate of 2,900 solar masses per year. It also contains about 270 billion times the mass of our sun in gas and nearly 3 billion times the mass of our sun in dust. “That’s a whopping large quantity of dust, considering the young age of the system,” noted Justin Spilker, a recent graduate of the University of Arizona and now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas at Austin

The astronomers determined that this galaxy’s rapid star formation was likely triggered by a close encounter with its slightly smaller companion, which already hosts about 35 billion solar masses of stars and is increasing its rate of starburst at the breakneck pace of 540 solar masses per year.

The researchers note that galaxies of this era are “messier” than the ones we see in the nearby universe. Their more jumbled shapes would be due to the vast stores of gas raining down on them and their ongoing interactions and mergers with their neighbors.

The new observations also allowed the researchers to infer the presence of a truly massive dark matter halo surrounding both galaxies. Dark matter provides the pull of gravity that causes the universe to collapse into structures (galaxies, groups and clusters of galaxies, etc.).

“If you want to see if a galaxy makes sense in our current understanding of cosmology, you want to look at the dark matter halo — the collapsed dark matter structure — in which it resides,” said Chris Hayward, associate research scientist at the Center for Computational Astrophysics at the Flatiron Institute in New York City. “Fortunately, we know very well the ratio between dark matter and normal matter in the universe, so we can estimate what the dark matter halo mass must be.

By comparing their calculations with current cosmological predictions, the researchers found that this halo is one of the most massive that should exist at that time.

“In any case, our next round of ALMA observations should help us understand how quickly these galaxies came together and improve our understanding of massive galaxy formation during reionization,” added Marrone.

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.