Lost but not forgotten

The call came on Good Friday, two months ago. They had found the plane, a B-24 bomber shot down over a remote Pacific Ocean bay during World War II. One of the 11 crew members on board was my relative. Through five years of research, our extended family had pieced together details of his last mission. Now we knew for certain where it ended, and the location of that loss could begin closing a wound that had opened up in my family 74 years before.

The journey that would lead to this discovery started during a needed break from my own academic research on news coverage of wartime casualties. Entering monthly casualty data from World War II into a spreadsheet for statistical analysis was harder than I expected. Each number weighed heavier than the four or five keystrokes needed to enter it. Every digit represented individuals with stories, and families, and futures they would never inhabit. Thousands and thousands of empty futures for every month of the war.

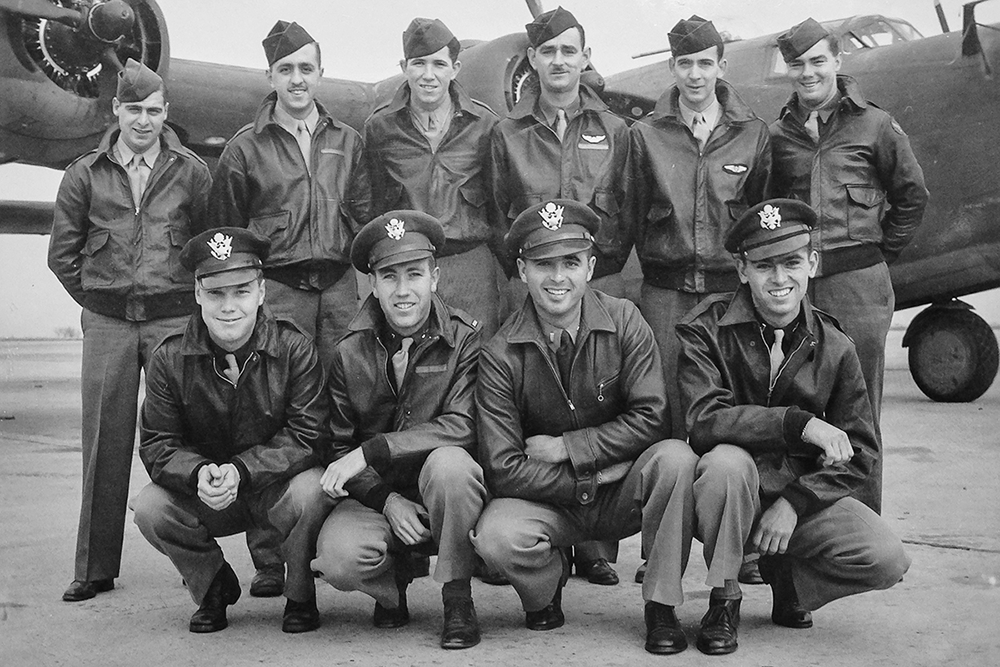

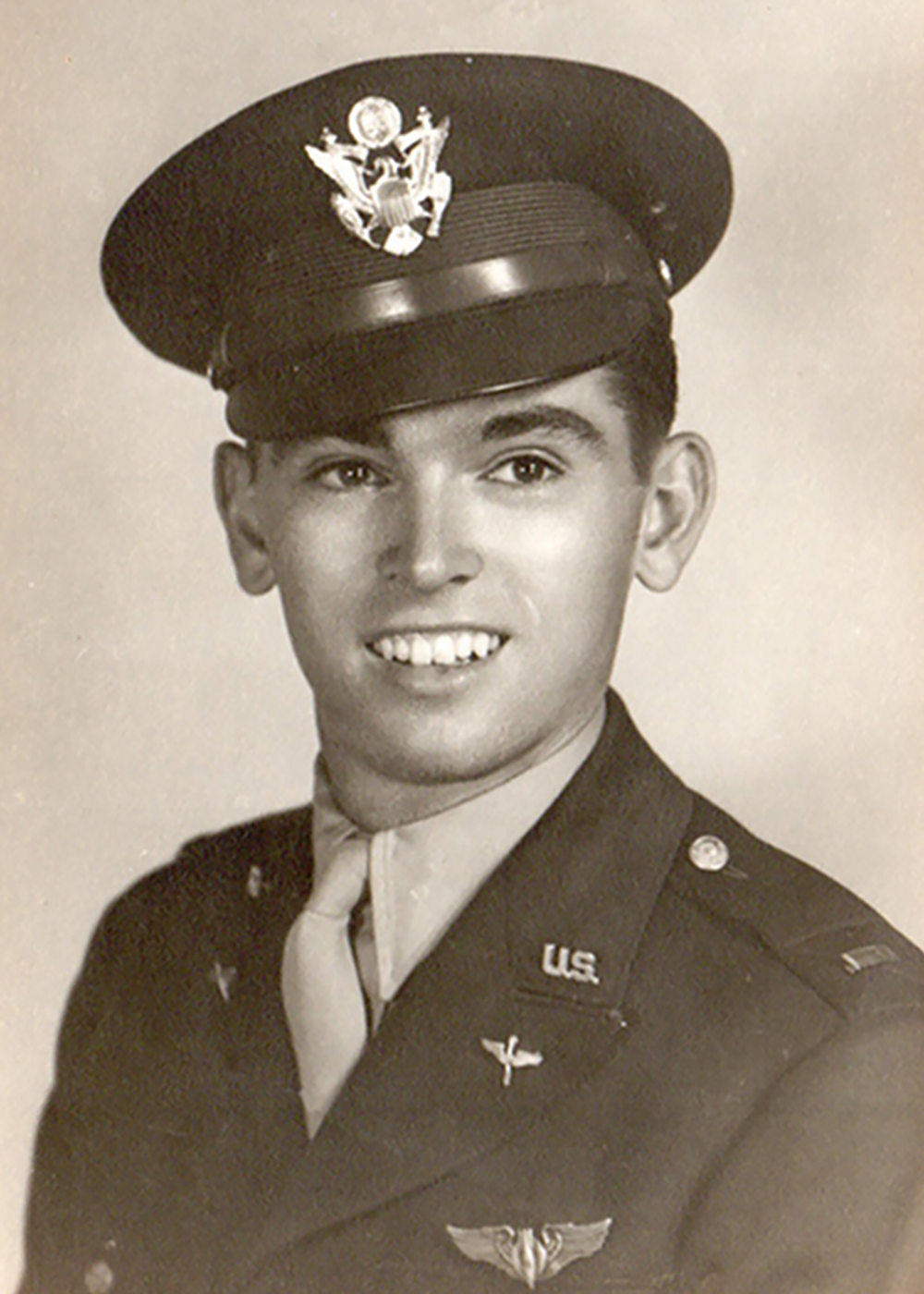

I decided to spend part of Memorial Day 2013 learning what I could about two of my relatives lost in that war. I knew so little about either of them that I even had to ask my parents for their names. One of them was my mother’s cousin, 2nd Lt. Thomas V. Kelly Jr. His friends called him Tom. He was the bombardier on a plane that went down during a mission against a Japanese

coastal base somewhere over Papua New Guinea in 1944. That was about all my family had ever been told.

I found a few leads through the internet, university databases and news archives. Within days, members of my extended family were involved. Over five years of on-again, off-again efforts, we would make contacts, track down sources, sift through endless photos and websites, research family genealogies, spend days in archives. Project Recover – the organization we eventually handed our research findings over to, and which would find the plane – says it had never seen a similar effort.

For many families, and definitely for ours, there had been a painful silence around this loss that carried through the generations. In the case of those declared Missing In Action – today there are still nearly 73,000 MIAs from World War II alone – you don’t have a body that comes home, and often little information. There is no closure.

But as we began to find out more about the circumstances of our relative’s loss – just a fragment of information here, a new scrap of detail there – we found ourselves being pulled into his story in a deeper way. And it drew our family together. We were spread across several states and rarely had much to say to one another before, but each new discovery became an opportunity for us to connect and learn more about our shared history.

Our success would not have been possible before the internet. There was also much serendipity involved. Behind it all was a large number of military history buffs around the world who were willing to answer emails from complete strangers. They sometimes had very specific and usually arcane knowledge for us, about things like the shape of engine cowlings and the dates of aircraft paint jobs. They graciously shared a sliver of what they knew, and that sliver was often absolutely critical for leading us one more step down the right path. This happened many, many times, and their generosity continues to amaze me.

When I got that call on Good Friday from Project Recover, I hoped the news would be encouraging but I did not expect to hear that they had found the plane. The Easter weekend that followed will be remembered by Tom’s extended family as a time of exhilaration and of grieving. The grieving really surprised us. Our relative died a long time ago, most of us never knew him, and the circumstances of his loss were by then familiar after five years of research. But up to that weekend he was a face in an old picture, a name on a memorial stone.

That weekend, thanks to Project Recover, Tom’s family saw images of his grave for the first time, right where it’s always been, 200 feet beneath the surface of Hansa Bay. And we were grateful. Grateful for Tom’s sacrifice, which is now once again a living memory for his extended family. Grateful for all of those people across the globe we’ve never met, people who helped us understand and embrace what Memorial Day is, and what it is for. And we are grateful that one empty future will never be forgotten.

Editor's note: Scott Althaus is the Merriam Professor of political science, a professor of communication, and director of the Cline Center for Advanced Social Research at the University of Illinois.