Looking Forward by Looking Back

Feng Sheng Hu, head of the Department of Plant Biology, was greeting new faculty on campus last fall when he met a professor of statistics. He asked politely about her work, expecting a lesson in probability or some other statistical concept, but to his surprise she began talking about something he’s been studying for years: climate change.

It turns out that Bo Li, the professor of statistics whom he met that day, specializes in statistical analysis of paleoclimatology, or the study of prehistoric climates. That was interesting enough, but Hu, a longtime professor on campus, realized something else. Over the past few years, the number of people on campus studying aspects of the ancient earth—the “paleosciences,” to use a broad term—has increased dramatically.

Sensing possibility, Hu, along with Jessica Conroy, a new professor of plant biology and geology, organized a pizza lunch to bring together people in paleo-related fields. Some 20 people showed up from across campus, including those in statistics, plant biology, geology, atmospheric sciences, anthropology, animal biology, and the Illinois State Geological Survey. About half had arrived on campus within the past five years, Hu says.

“There is a major emphasis on studying the past, because if you don’t know the past you can’t say whether what’s going on today is unusual or not,” he says. “I always use this quote: ‘The past is a window to the future.’”

Hu feels that Illinois is becoming one of the strongest campuses in the country for paleo-related research. He’s organized a lectureship in honor of Tom Phillips, professor emeritus of paleobotany, in part to recognize Phillips’s vast contributions to the field, but also to help highlight the growing paleo-related programs at Illinois. Andrew Knoll, a highly respected paleobiologist from Harvard University who has called Phillips his “hero,” will be the first lecturer, on October 30.

“I think the scope of expertise we have on campus now is really pretty tremendous,” Hu says. “In the old days, most of the paleo people would have been studying fossils. And fossils are fascinating, and we still have people studying fossils here. But we also have people working on paleo questions from very different angles.”

Li came to Illinois from Purdue University, after she had done research at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Colorado. She is one of the first statisticians to begin studying the mountains of data that scientists are generating through their studies of paleoclimate.

For example, tree rings, pollen, fossil corals, lake sediment, and speleothems—mineral deposits in caves—all indicate changes in climate. Even air bubbles deep within ancient ice tell a story, as they indicate what the atmosphere contained thousands of years ago. But each of these indicators only tells part of the story, and Li integrates and analyzes the data to take advantage of the strength of each indicator, find their coherent patterns, and characterize the ancient climate and how it changed.

After the recent luncheon, Li saw several new research possibilities emerge with cohorts on campus, from ecologists to atmospheric scientists.

“I was surprised that so many people on campus are working on paleo-related research,” she says. “I would really like to work with some of them. They are really good researchers, and very active.”

Stephen Marshak, director of the School of Earth, Society, and the Environment, agrees that the interest in climate change is fueling much of the growth in paleo-related fields. He adds, however, that there are other factors raising interest in the paleosciences. For example, the question of whether there’s life on Mars is adding intrigue to what the earliest life on Earth looked like. There’s also interest in ancient mass extinctions, and whether the extinctions of recent years means that modern Earth is actually in the midst of a so-called “Sixth Extinction.”

And in anthropology, there’s growing interest of how early humans interacted with the world around them.

“There are all these people from across campus who, while not being in the same field directly, have overlapping interests,” Marshak says. “And there are benefits to having folks get to know each other, because there are resources they can share. Sometimes it’s laboratory facilities that can make certain kind of measurements. Sometimes its field expertise, and sometimes it’s just disciplinary expertise that can lead to researchers making connections that might not otherwise have been made.”

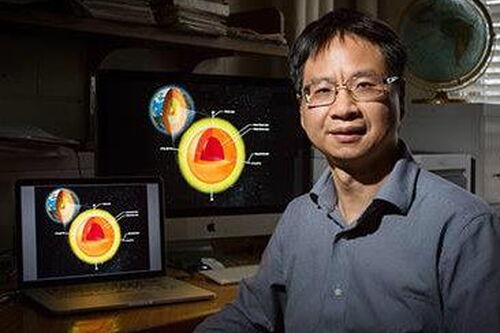

Conroy travels to places such as the Galapagos Islands and the Tibetan plateau to study lakes and how they reflect climate change. She and her research team plunge hollow tubes into the bed of the lake, fill them with sediment, and then analyze the sediment cores to assess changes in the biologic and chemical properties of the sediment through time. These changes often reveal variability in climate variables such as temperature and precipitation.

She is presently teaming up with researchers in geology and atmospheric science to understand how changes in oxygen isotopes—one chemical property of sediment cores—might reveal climate change. Even though paleo-related fields can be very different, Conroy says they coincide in enough ways to create huge potential for working together.

“We all speak the same language, I guess you could say,” she says. “Science has gotten so specialized, but we’re all here together, and we can definitely talk, collaborate, and share ideas. It’s very exciting.”