Rethinking the historical record in the age of social media

The nature of what counts as the historical record, and how it is made, is rapidly changing. Through social media and other methods, people are quickly becoming accustomed to digitizing and sharing the events of their lives at a furious pace—and relying upon the Internet as a kind of vast historical archive.

It’s a trend that greatly concerns historians, librarians, archivists, and information scientists who are now grappling with the shifts in how documentary sources are created and shared, and how events of the modern era will be recorded for future generations.

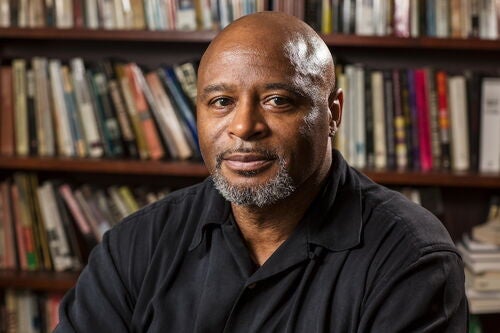

“The long term question of how the digital environment we live in today will be preserved is very much up in the air,” said John Randolph, a professor of history at Illinois.

Thanks to a $138,360 grant from the Humanities Without Walls Consortium, all of these issues will be the subject of a three-year, multi-institutional research project. Students, faculty, and staff from Illinois, Michigan State University, and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln will investigate what role higher education can play in the making of the historical record of the future.

Not all of these issues are technological, Randolph said.

“On one hand, you do have the rise in digital culture,” he said, “yet there’s also a shift in the kinds of histories people are interested in, moving beyond political and national narratives into the fields of social history and cultural history. So the question isn’t only how we can help digitize and interpret traditional kinds of documentation, but how we can help shape what counts as a source in the first place.”

Then there are questions about the reliability of things we find online, and whether they truly help us better understand the past. For instance, while sites such as YouTube and Facebook allow for the creation of images, video, and film, Randolph said they often decontextualize the objects they share. Whereas traditional institutions such as libraries, archives, and museums provide information about origins and authenticity, much of that information gets lost in the digital sphere.

“Most of these sources online don’t provide for stable preservation and don’t mention how others could look at this object. There’s no citation framework and no checks for authenticity,” Randolph said. “If instructors want to use a World War I film that has been digitized and presented on YouTube, they often face painfully basic questions like, ‘Is this actually a historical film? Or just something some random guy created in Photoshop? How much of it do we have? Where did it come from?’”

Much of this new historical record, Randolph added, is being built on proprietary platforms provided by IT corporations, such as Facebook and Twitter. Their primary aim is to commercialize private data, rather than to preserve and sustain knowledge of the past, Randolph said.

“I think Facebook and Twitter are emblematic of both the promise and the challenges documenting history in a digital environment,” Randolph said. “On the one hand, there’s no question that future scholars who want to understand different events, such as what happened in Charlottesville last year, are going to find that Twitter streams, the images, the film that was shared through Twitter, to be invaluable. But one question is, who is collecting all of that? And then there’s the question of, what do we need to know to be able to use that information responsibly and critically. We want to figure out how people can learn to contextualize a historical record that doesn’t always provide that context for us.”

The three institutions in the newly funded project will develop curricula for documentary and data literacy work in the 21st century. The goal is to partner with students to create better models for producing, preserving, and publishing the past.

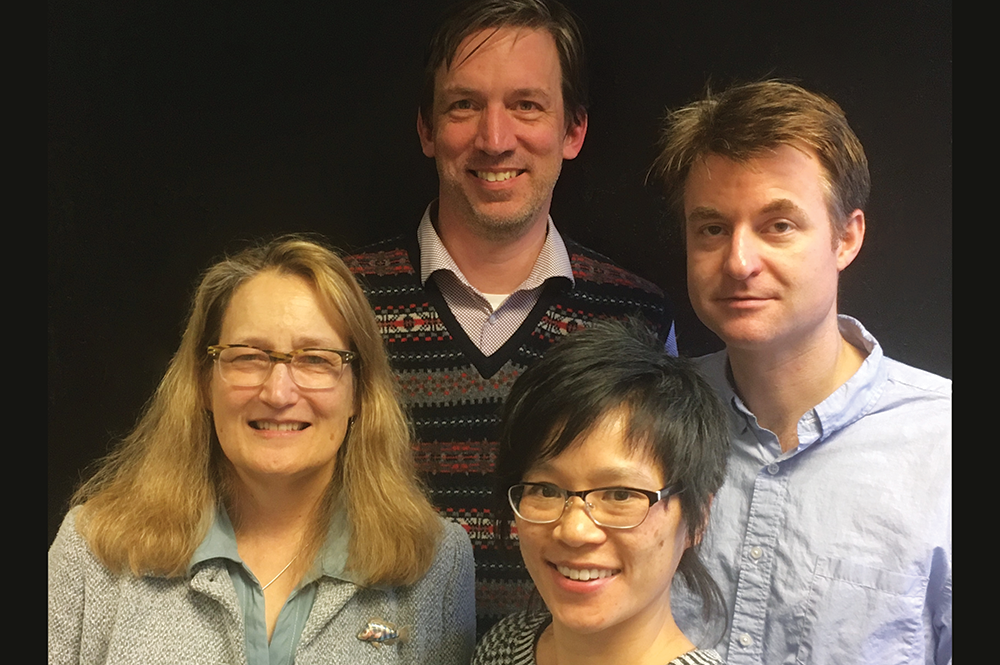

At Michigan State University, Sharon Leon and Brandon Locke from the Lab for the Education and Advancement in Digital Research will develop a curriculum to teach students how to produce and analyze historical data. At the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Patrick Jones, William G. Thomas, and Aaron Johnson will work with K-12 teachers to bring their innovative digitization project “History Harvest” to Nebraska public schools.

Scholars at Illinois, meanwhile, are building a curriculum that works across the entire life cycle of sources, from selection to preservation to publication and use. Researchers will work with communities interested in preserving their own pasts, in ways that have meaning to them, even as they also engage with the question of what to do with records that have been created and shared through information technology.

Kathryn J. Oberdeck, professor of history, Daniel Gilbert, professor of labor relations, Bonnie Mak, professor of information sciences, and Randolph will lead the group in Urbana-Champaign.

Humanities Without Walls funds will be used to support the work of graduate and undergraduate students on the project. In particular, graduate students in history, education, and the information sciences will be made lead researchers on the project, as part of a special laboratory practicum. Working together, they will collaborate across institutions to develop documentary applications, skills, and practices that they can use in the future.

The grant will also allow the team to conduct workshops to discuss the results of their experiments and present ideas. The group also intends to share its applications and model curricula through journal publications and open educational resources.

Randolph said they are grateful to the Humanities Without Walls Consortium and it’s funder, the Mellon Foundation, for allowing researchers to address this complex and important challenge.

“What I think is important about this initiative is that it brings the strengths of these research universities to bear on a really public problem,” Randolph said. “What kind of historical record do we want in the future? What role should higher education play in its making? And how can we integrate that into the work we do in the classroom?”