Virtual predator is self-aware, behaves like living counterpart

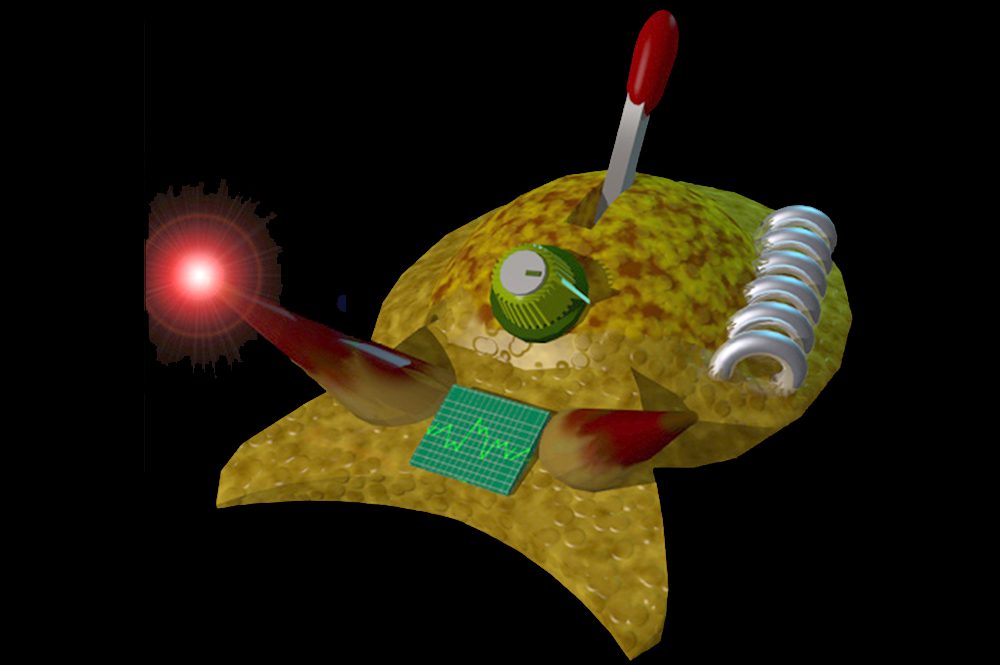

Scientists report in the journal eNeuro that they’ve built an artificially intelligent ocean predator that behaves a lot like the original flesh-and-blood organism on which it was modeled. The virtual creature, “Cyberslug,” reacts to food and responds to members of its own kind much like the actual animal, the sea slug Pleurobranchaea californica, does.

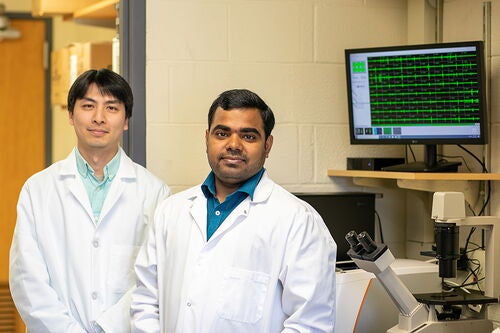

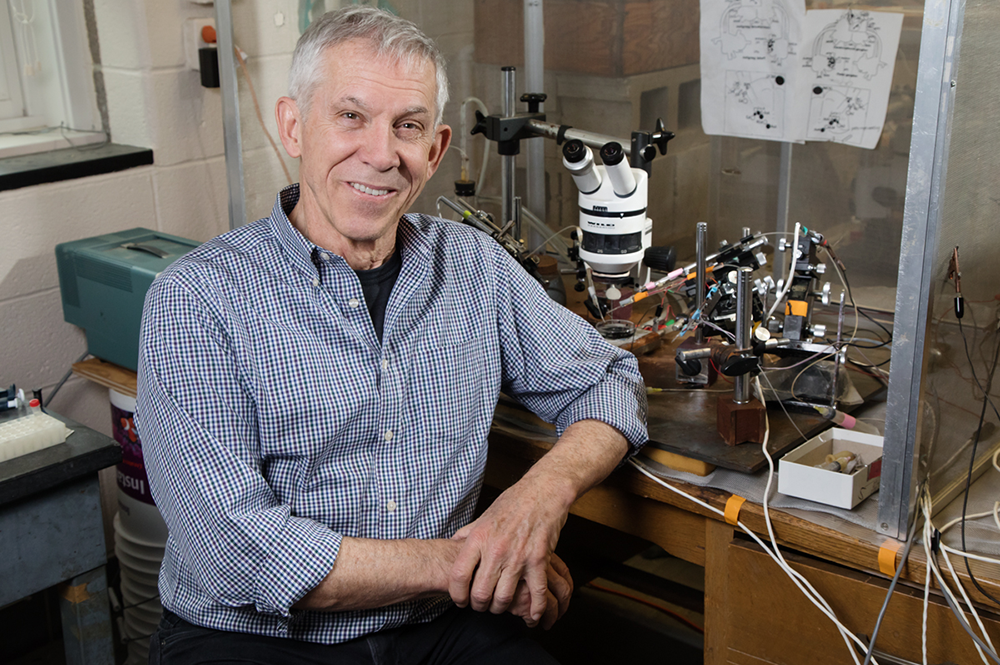

Unlike most other AI entities, Cyberslug has a simple self-awareness, said University of Illinois molecular and integrative physiology professor Rhanor Gillette, who led the work with software engineer Mikhail Voloshin.

“That is, it relates its motivation and memories to its perception of the external world, and it reacts to information on the basis of how that information makes it feel,” Gillette said.

Cyberslug knows when it’s hungry, for example. It also has learned which other kinds of virtual sea slugs are yummy to eat and which are less desirable.

Sea slugs typically choose one of three responses when encountering another creature in the wild, Gillette said. “Do I eat it? Do I mate with it? Or do I flee?”

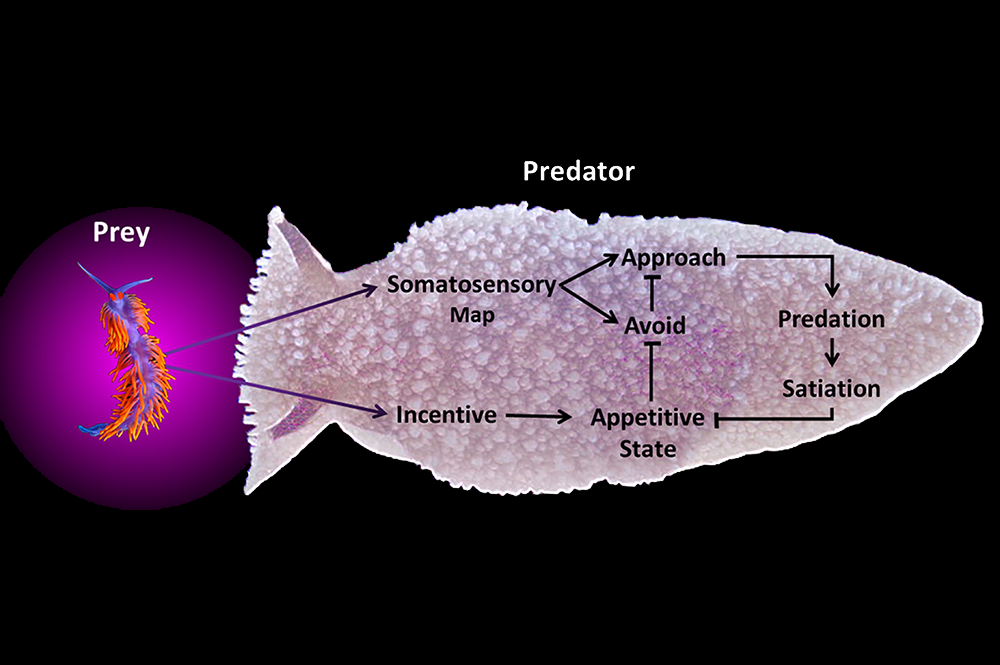

To make the right choice, they must be able sense their own internal state (Am I hungry?), get cues from their environment (How does it smell?) and remember past encounters (Did this thing sting me last time?).

“Their default response is avoidance, but hunger, sensation and learning together form their ‘appetitive state,’ and if that is high enough the sea slug will attack,” Gillette said.

"When P. californica is super hungry, it will even attack a painful stimulus,” he said. “And when the animal is not hungry, it usually will avoid even an appetitive stimulus. This is a cost-benefit decision.”

Cyberslug behaves the same way. (Run a Cyberslug simulation here.)

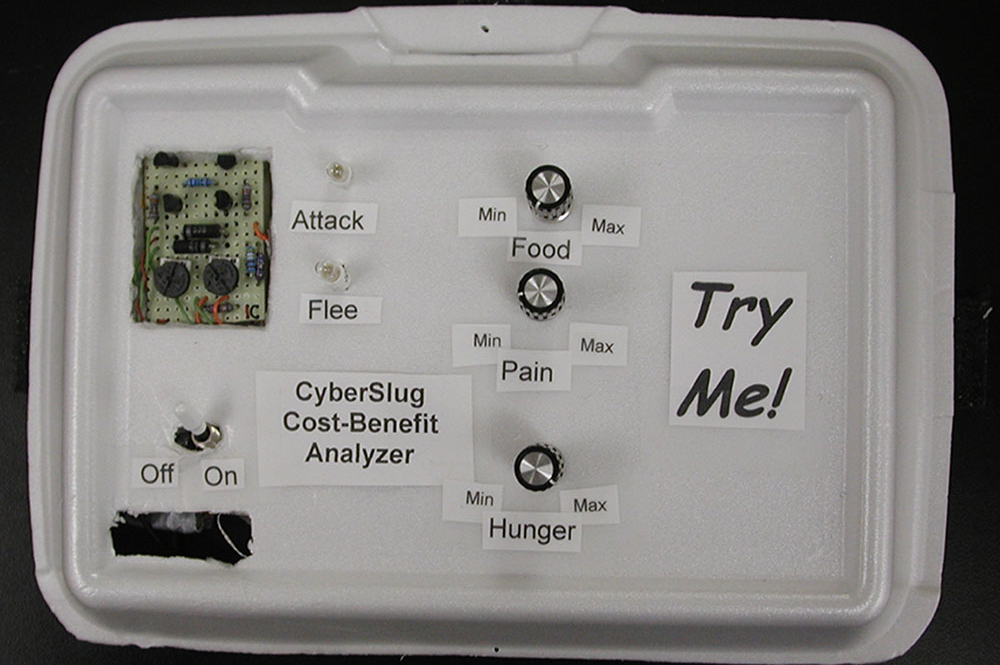

In previous work, Gillette and his colleagues worked out the brain circuitry that allows sea slugs to operate in the wild, “down to individual neurons,” he said. To test the accuracy of their models, the researchers experimented with simple computer simulations. One of the first circuitry boards Voloshin built to represent the sea slug brain was housed in a plastic foam food takeout container.

The new model uses more sophisticated algorithms to simulate Cyberslug’s competing goals and decision-making, Gillette said. Over time it learns what is good – and not so good – to bite. Just like P. californica, the more it eats, the more satiated it

becomes and the more likely it is to avoid other creatures. But as hunger returns, Cyberslug becomes a less picky eater.

“I think the sea slug is a good model of the core ancient circuitry that is still there in our brains that is supporting all the higher cognitive qualities,” Gillette said. “Now we have a model that’s probably very much like the primitive ancestral brain. The next step is to add more circuitry to get enhanced sociality and cognition.”

Local co-authors of the study also include medical information science professor Jeffrey Brown and graduate student Ekaterina Gribkova, of the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology at Illinois.

The National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health supported this research.