Wassaja: A bridge between worlds

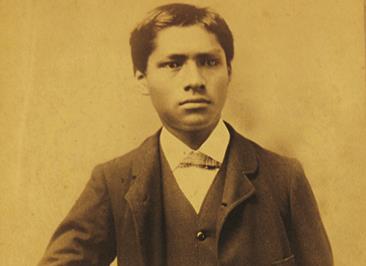

Life was hard in southern Arizona in the 19th century, and there wasn’t much reason to expect that a young boy named Wassaja would long be part of it when he was dragged into the mountains by enemy raiders in 1871. Certainly there was no reason to expect that 145 years later a building at the University of Illinois would be named in his honor.

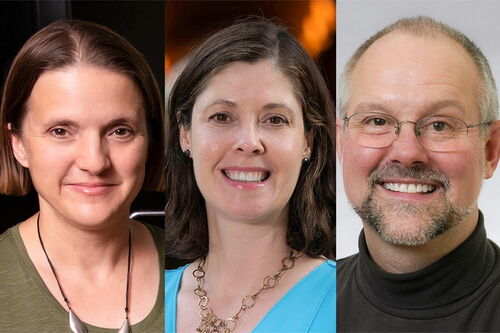

Last fall, however, Illinois dedicated Wassaja (WAHS-ah-jah) Hall, a residence building that houses some 500 students, after the university’s first Native American graduate. The ceremony included members of the Fort McDowell (Arizona) Yavapai Nation Tribal Council—including several of Wassaja’s descendants.

“Besides the value of education, Wassaja taught us that despite our own small size, we can move mountains,” said Bernadine Burnette, president of the tribal council.

As Wassaja waged a successful fight for Native American rights, he had a deep understanding of America’s widely separate cultures during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Much of that understanding was forged during his time as a student at the University of Illinois in the early 1880s.

How did Wassaja come to study at Illinois? The story begins after Wassaja—whose name means “beckoning” in his native Yavapai language—was kidnapped by Pima raiders, when he was offered for 30 silver dollars to Carlo Gentile, an Italian photographer. Gentile felt a connection with the boy and adopted him as his own son, renaming him Carlos Montezuma.

The pair spent the next few years moving around the country, with Wassaja even playing a theatrical role with Buffalo Bill in the early 1870s. Wassaja was a promising student, however, and Gentile, realizing that his adopted son needed a stable home to complete his education, placed the boy in the care of Baptist minister William H. Steadman, of Urbana, according to “The Remarkable Carlo Gentile: Italian Photographer of the American Frontier.” (Years later, Steadman would officiate over the wedding of Wassaja and Marie Keller, a Romanian-American.)

Wassaja graduated with honors from Urbana High School and enrolled at Illinois in 1880, when he was only 14 years old. According to accounts, he excelled in a variety of courses at Illinois, and he honed his debate and oratorial skills as a member of the Adelphic Society. He also proved popular among his classmates, who endearingly called him “Monte,” according to a story in the Public i, and he was elected president of his senior class.

The university was so impressed by him that it waived Wassaja’s matriculation fees, and Wassaja earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1884. He went on to the Chicago Medical College, becoming the first Native American male to earn a medical degree.

“I think (Wassaja) was accepted in this community,” Jamie Singson, director of U of I’s Native American House, told the News-Gazette. “He really is a son of Urbana. He not only belongs to the University of Illinois but he belongs to the Champaign- Urbana community.”

Wassaja never forgot Illinois, as he corresponded with his alma mater regularly for years after he left Champaign-Urbana. He also drew upon his education extensively. Wassaja became a physician for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, but increasingly he became dismayed with the agency after witnessing poor management of reservation facilities. He would eventually leave the bureau to begin a private practice in Chicago, but he was compelled to fight for the land and water rights of his native Yavapai tribe.

The issue would consume the rest of his life, as by the early 1900s Wassaja was nationally recognized as a passionate Native American leader. In 1911, he led a successful fight to defeat a bureau plan to relocate his native Yavapai tribe from Fort McDowell, according to the Encyclopedia of World Biography. A few years later, the bureau once again tried (and failed) to relocate the Yavapai, as Wassaja’s resistance to the idea was so strong that he once nearly came to blows with bureau officials.

According to a 1916 issue of American Indian Magazine, he delivered a rousing speech in 1915 at the Society of American Indians Conference in Kansas, where he declared, “We must act as one. Our hearts must throb with love—our souls must reach to God to guide us—and our bodies and souls must be used to gain our people’s freedom. In behalf of our people, with the spirit of Moses, I ask this: The United States of America—let my people go.”

In 1916, Wassaja began publishing Wassaja: Freedom’s Signal for the Indians, a newsletter devoted to addressing the future of Native Americans. He continued this until the end of his life, 1923, when he died of tuberculosis at Fort McDowell.

Wassaja died in a simple hut, but his legacy has inspired others for years. In the tiny community of Fort McDowell, residents have named their health clinic after Wassaja, and the community has helped create several academic scholarships in his name.

“If not for Wassaja’s efforts,” said Burnette, “it’s safe to say there wouldn’t be a Fort McDowell.”

During the dedication of Wassaja Hall, Barbara Wilson, executive vice president and vice president for academic affairs for the U of I System, said it’s hard to think of anyone who exemplified the Illinois story as well as Wassaja.

“His Illinois experience didn’t just give him a degree or education,” she said. “It made him a leader, and that’s what we hope for all our students.”

*Editor's note: This story originally appeared in LAS News magazine (Spring 2017).